INTRODUCTION

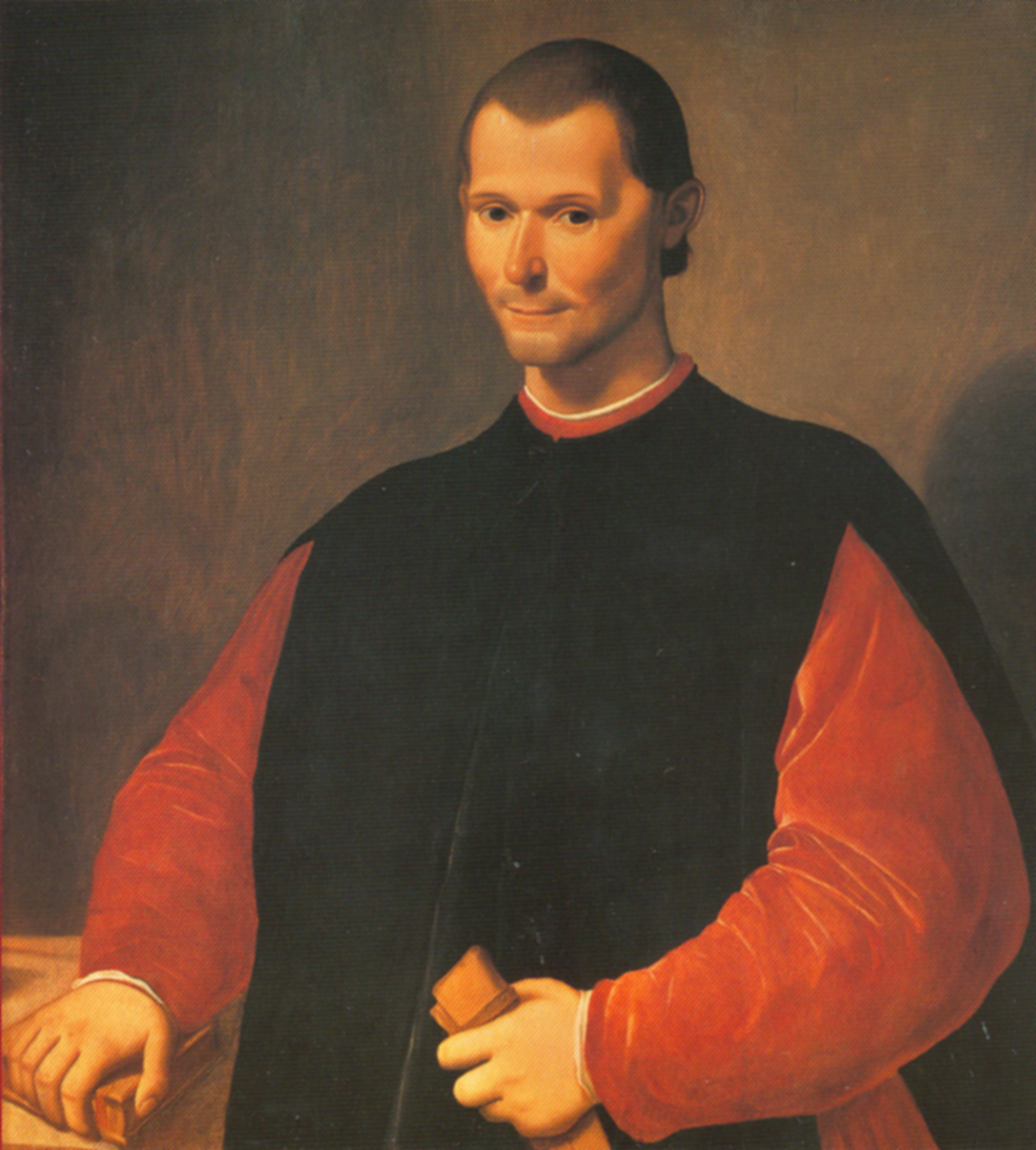

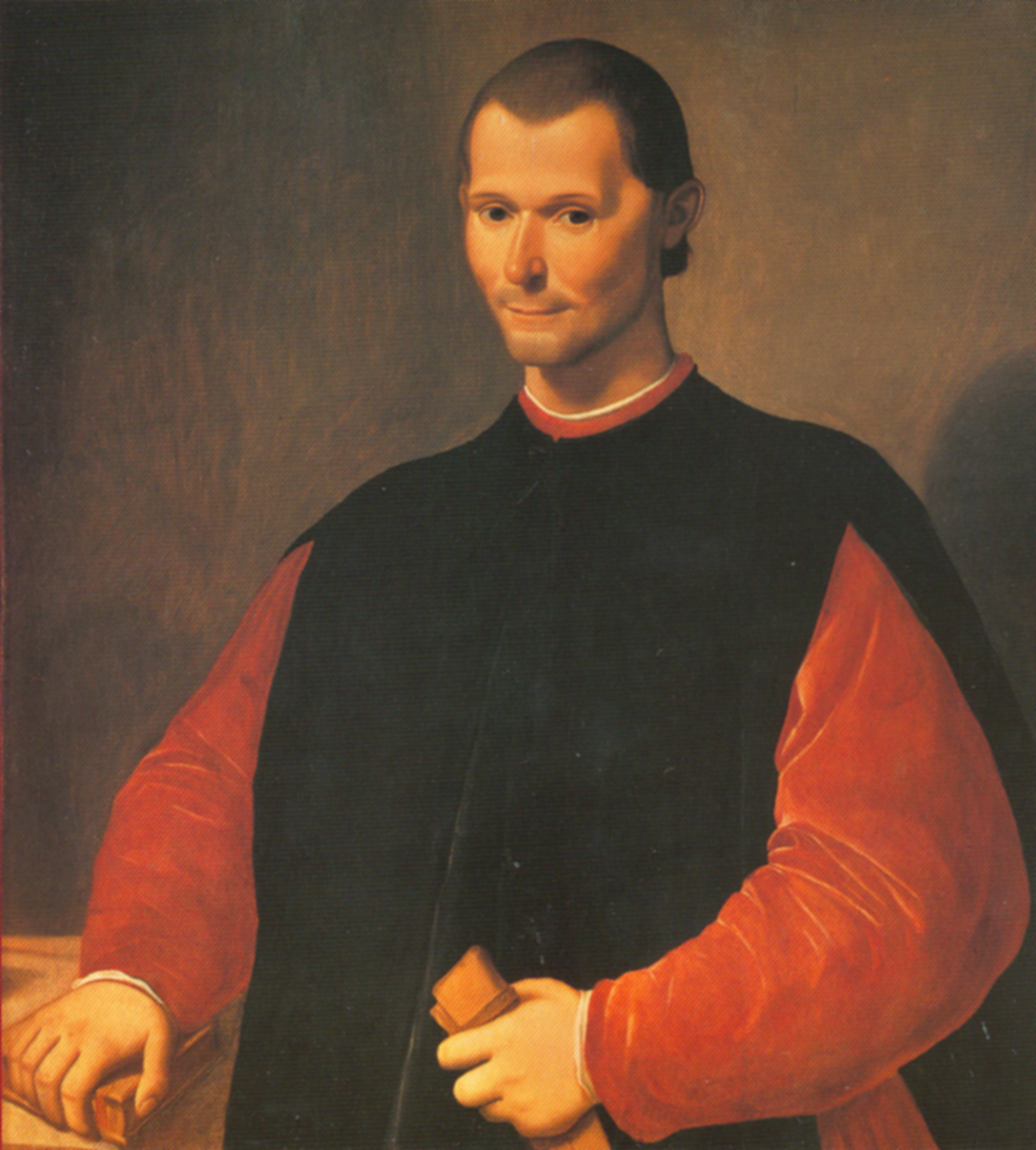

Niccolo Machiavelli’s works are classics of international relations, implicitly if not explicitly regarded as timelessly insightful. The Prince and The Art of War critique mercenaries in depth. Mercenaries’ became drastically less prominent in the centuries after the development of the state and popular standing armies, but the recent resurgence of mercenaries begs the question of whether Machiavelli’s work can help inform analysis of present day mercenaries. Although mercenarism remains a marginal issue, it may present a unique challenge to sovereignty and the rule of law. Although broader arguments about the changing character and problematic traits of mercenaries are examined here, examples drawn from Sierra Leone help to inform my analysis of the small set of recent cases in which mercenaries have been recruited by weak states to defend themselves. The first issue that must be addressed is how mercenarism can be defined, and to what extent the resurgent “mercenaries”, alternatively referred to as private security companies or private military companies, match this definition. An assessment of the basic turning points in the history of mercenarism may also prove helpful in assessing the generalizability of Machiavelli’s conclusions and mercenary involvement in Sierra Leone across time. Speaking of which, the significance of the Sierra Leone case compared to other contemporary examples can be demonstrated by reviewing a database of Private Security Companies’ post-Cold War involvement in weak states. After laying this groundwork, the most controversial aspects of mercenaries may be addressed, and compared—where possible—to Machiavelli’s critique. Mercenaries alleged greed can be assessed in terms of whether they charge exorbitant fees or attempt to seize the very concrete interests they are employed to defend. The combat effectiveness of mercenaries should also be assessed both in terms of their aversion to conflict and their conduct when they do fight. Last but not least, mercenaries might challenge the legitimacy of the state. Finally, these problematic characteristics of mercenaries must be compared to those of national militaries in weak states, to determine whether these characteristics are unique, and whether mercenaries may present the lesser of two evils in the event that national armies are sufficiently unprofessional.

JUSTIFYING METHODS

*Clarifying Terminology

Mercenaries can be defined, in simple terms, as individuals or groups who fight for money on behalf of foreign states (Grundy 296). Although Post-Cold War companies fought for corporate mining concessions instead of cash alone, the basic concerns surrounding forces fighting for personal enrichment instead of ideals remain (Francis 322, 324). A key discriminating element of this definition is “fighting”, given that engaging in military operations directly is only one of a variety of roles private military and security companies may perform (Joenniemi 191-192). Private security companies may be distinguished from private military companies in that the former provide indirect military support from a static location. Moreover, Joenniemi distinguishes between “blue collar” mercenaries actually fighting in conflicts, predominating in Africa, and “white collar” training, logistics, and equipment specialists more prevalent in the Persian Gulf region (Joenniemi 191). The latter function of private military companies is an emergent result of accelerating military innovations (Joenniemi 195) distinct from the more timeless phenomenon of mercenarism, and as such is not the primary focus of this work, even if private military companies directly involved in warfighting are now in the minority (Francis 323).

*Importance of Research

Mercenarism “is as old as warfare itself”, but that does not necessarily mean the challenges presented by a new wave of Afro-centric mercenary interventions--beginning with the 1964 intervention in the Congo—are comparable to those identified in the distant past (Francis 320). A “historical perspective” interprets mercenaries’ recent actions, concentrated in Africa, as being driven by the same factors as mercenary activities in other places and times, but this view fails to recognize that the environment in which mercenaries operate has changed over time, so the concerns surrounding present day mercenaries differ in significant ways from those raised in the distant past (Joenniemi 184-185). Though these factors remained mostly static in the past, the present environment features constantly changing economic and political circumstances, as well as changes in the character of “the international system”, which cannot be ignored when problematizing the new private military companies (Joenniemi 185). With globalization, mercenarism—and conflict in general—has become predominantly “intra-societal”, while liberal norms have imposed consequences on controversial actions, and rapidly developing technologies have placed a new emphasis on maintaining technical superiority (Joenniemi 185). The late 20th century has witnessed the emergence--or resurgence—of private military companies, but the increasingly influential and normalized corporate character of Post-Cold War private military companies may distinguish them even from earlier Post-World War Two mercenaries (Francis 322, 324), which might be interpreted as opening them to greater external regulation (Creehan 7), and represent a sign that contemporary mercenaries will engage in “self-regulation”, preventing them from taking controversial actions (Creehan 6). In contrast, Patterson argues that the corporate nature of contemporary mercenaries suggests a greater emphasis on profit, which is incompatible with idealistic humanitarian restrictions on conflict (Patterson 168).

Although mercenaries remain largely outside the jurisdiction of states and international organizations alike (Aguilar 5), the mercenaries of Machiavelli’s time were abandoned due to the threat their unrestrained violence posed to the state’s trade interests (Joenniemmi 188) contemporary corporate mercenaries are likely to share the states concern for preserving trade.

*Rationale for Case Selection

In order to identify the set of Post-Cold War mercenary contracts most pertinent to Machiavelli’s critique, data (Collaborative Research Center Berlin) on private security companies involvement in “failing states” (Branovic) was used to identify cases in which mercenaries were hired to perform “Combat and military operations”, defined as cases in which “armed private actors are directly involved in military operations and fighting” (Branovic). The other roles for private security companies coded in the original dataset were “Military assistance”, “Operational support”, “Logistics support”, “Intelligence”, “Quasi-police tasks”, “security/protection”, “Police advice and training”, “Demining”, “Humanitarian aid”, “Weapons disposal/destruction”, and “facility and infrastructural build-up” (Branovic). The list of cases was further narrowed to only those where mercenaries were employed to fight for their employers within the employers’ own territory, so as to avoid confusion with the “auxiliaries” Machiavelli contrasts with mercenaries.

The remaining subset of cases comprised Angola, Columbia, Congo-Kinshasa, Ethiopia, and Sierra Leone. Only a single contract with mercenaries was made by Columbia in 2001 and Ethiopia in 1998 (Collaborative Research Center Berlin). Given the greater prevalence of contracting of private security companies by the other three states—3 contracts with a total of 3 companies by Congo-Kinshasa, 4 contracts with a total of 8 companies by Sierra Leone, and 6 contracts with a total of 7 companies by Angola (Collaborative Research Center Berlin)—they seem more useful cases for analysis. Notably, all contracts were in consecutive years for each country in this subset of the data (Collaborative Research Center Berlin), suggesting that they may represent unitary cases. The case of Sierra Leone—unique in that it issued the most contracts and did not share the DRC and Angola’s tumultuous history of mercenaries earlier in the twentieth century—will be the primary case in this assessment of Machiavelli’s generalizability, but Angola and Congo-Kinshasa are likely fruitful targets for further analysis.

Approximately 58 Gurkha Security Guards were hired to defend private assets belonging to the American-Australian corporation known as Sierra Rutile and train regular military forces for Sierra Leone in February 1995 (Fuchs 107; Francis 326). Gurkha Security Guards were replaced in March by Executive Outcomes (EO) mercenaries tasked with waging military offensives in addition to providing training and logistics support to native forces, (Francis 326; Fuchs 108). Executive Outcomes was also responsible for the security of Sierra Rutile and Branch Energy’s mining assets through its subsidiary, Lifeguard Security(Francis 324). Approximately 100 Executive Outcomes personnel were initially employed by the Sierra Leonean government, but this number tripled at its peak (Fuchs 108). Brigadier Burt Sachs led the Executive Outcomes mercenaries, but argued that their main priority was training Sierra Leonean forces so that they could maintain stability in the long term (Francis 327). The last major private military company employed by the Sierra Leonean government was Sandline, which acted in a combat support capacity, somewhere between Gurka Security Guards and Executive Outcome’s roles. Sandline made an effort to train Sierra Leonean military forces just like the others, but it also contributed to the intelligence, plans, and coordination of operations, and it also provided both air support and logistics support, including controversial large scale armament involving $10,000,000 worth of weapons and ammunition (Fuchs 111; Francis 328). Although it does not engage in actual combat, Sandline has in practice been regarded as a mercenary force, like Executive Outcomes, on the grounds that its direct support for operations achieves significant strategic effects (Francis 324).

PROBLEMATIZING MERCENARIES

*Prohibitive Expense

All of the other threats posed by mercenaries will be particularly poignant if mercenaries also charge an exorbitant fee for the pleasure. Grundy argues that Machiavelli found mercenaries’ failings particularly outrageous because he was operating in the context of mercenaries so expensive that they threatened to bankrupt their employers, while present day mercenaries are more affordable (309). However, Grundy conflates mercenaries and auxiliaries, which have always been inexpensive “financially speaking,” but politically problematic (Grundy 309) given that they are, by definition, paid by a foreign power (The Prince 48). Still, contracts with mercenaries in time of need may be more affordable than large, standing national armies, which explains why just a few decades before Machiavelli produced The Prince, as conflicts began to demand greater numbers of men, European sovereigns consistently resorted to mercenaries (Joenniemi 187). Of course, Machiavelli’s militias would similarly address this concern (The Art of War 29-30).

The case of Sierra Leone clearly demonstrates how the financial burden imposed by mercenaries on their employers can prove overwhelming, especially in the present context of mercenaries concentrated in weak, impoverished states. The clear-cut dependency of mercenary service on payment makes them unreliable (Aguilar 5), as demonstrated when the International Monetary Fund (IMF) withdrew a loan Sierra Leone was counting on to pay Executive Outcomes, because IMF opposed the use of mercenaries (Creehan 6). Even in cases where payment can be sustained, payments to mercenaries may divert the bulk of funds needed for the state’s development of its own institutions (Aguilar 5), which represent less transient defenses. Indeed, the cost of paying Executive Outcome was equivalent to the entirety of Sierra Leone’s national income (Olonisakin 146) Executive Outcomes was contracted by sierra leone twice over the course of the conflict, in 1995 and 1996, imposing a total cost of $35,200,000—or $1,225,000 per month (Francis 326) for a total of 21 months (Francis 331)—far more than Sierra Leone could pay at the time. The government agreed to periodically make payments until its $19,500,000 debt was paid in 1999 (Fuchs 109; Francis 331), thereby extending the financial burden well after the mercenaries left but the security challenges they had defended against endured (Fuchs 118).

It could be argued that mercenary groups like Sandline (Creehan 6) and Executive Outcomes (Francis 331) are comparatively affordable given that they charged the government of Sierra Leone much less than the amount spent by external actors on a United Nations observer force. However, when those who employ mercenaries are unable to afford any alternative, mercenaries may be able to extort clients by threatening to abandon their clients (Aguilar 5), as Executive Outcomes did when the government of Sierra Leone was late in making a payment (Francis 332). More fundamentally, these comparisons neglect to address the mining concessions mercenaries received.

*Seizure of Contested Resources

If mercenaries are driven solely by greed, they might attempt to seize the very valuables they are charged with securing for their employers. Machiavelli noted that mercenaries may unilaterally decide to occupy and loot territory within the warzone indiscriminately for their own personal enrichment, which he referred to as erecting a “flag of fortune” (The Art of War 14). One broad lesson to draw from this is that mercenaries may seize the very assets they were hired to secure for their employers in a conflict. The contested issue driving the Sierra Leone conflict is itself contested, with some scholars claiming the war was driven by political grievances (Fuchs 106), and others claiming it emerged from competition over the control of the countries immense resource wealth (Aguilar 5; Francis 324). Regardless of whether it was the central point of conflict for regular forces, mineral wealth became a key advantage once the war began. Despite the illicit nature of Sierra Leonean conflict diamonds under an international embargo, they provided the bulk of the funding for both the rebels and government in the Sierra Leonean war, as private militaries and mining companies alike profited immensely from the diamonds (Aguilar 5; Fuchs 106).

While the strategic advantage of controlling the diamonds was significant (Fuchs 109), it is possible that the mercenaries became overly focused on this dimension of the conflict (Francis 322), given that it was an interest they shared with their employer (Francis 329), while their loyalties are more typically divided between their employers and their shareholders (Francis 333). By securing diamond mines for the government, mercenaries increased the government’s ability to pay them, but they were also increasing their own expected profits from the mining concessions the government awarded to the mercenaries less controversial corporate affiliates (Fuchs 108; Francis 322), as a desperate alternative to paying with money they didn’t have. Subsequently, Executive Outcomes identified securing diamonds in the Koidu area alone as one its three main objectives, alongside driving the rebels from the capital and eradicating the rebels’ central headquarters (Francis 327).

Nothing as blatantly perfidious as Machiavelli’s “flag of fortune” example was perpetrated by mercenaries in Sierra Leone, but the resource rights they procured amount to the plundering of a foreign nation’s wealth, undermining the long-term security of Sierra Leone. Sierra Leone is one of many countries afflicted by the “resource curse”, having neglected other forms of development for decades (Francis 324) due to its ability to rely on minerals for “two-thirds of export income” (Fuchs 109), thereby creating an unsustainable “rentier system” (Francis 335).

Mercenaries fixation on gaining control of natural resources is not unique to Sierra Leone (Fuchs 105). Francis goes so far as to use it as the basis for distinguish the new private military companies of the present from those of the past. “This new breed of mercenaries is not the traditional 'Dogs of War'- 'they are more of an advance army wanting to exploit the world's mineral resources” (Francis 322). He also argues that the greater tendency of mercenaries to accept contracts from resource rich nations is an indication that these resources are becoming the only payment that will appeal to mercenaries (Francis 331).

*Dubious Warfighting Efficacy

Before judging mercenaries ineffective, both their capabilities and level of commitment must be assessed. Machiavelli argues that mercenaries are unreliable because they will flee from genuinely threatening enemies, given the absence of any incentive to fight beyond their own self-interest (The Prince 43). Similarly, Joenniemi argued that mercenaries become increasingly unreliable as combat becomes increasingly deadly (189-190). The conflict in Sierra Leone represents a costly conflict, with casualties including 75,000 dead (Fuchs 106), and the behavior of Gurkha Security Guards seems to support Machiavelli’s criticism. Despite their attempts to avoid becoming involved in combat directly, Gurkha Security Guards forces lost two important officers along with twenty of their soldiers after blundering into a firefight and withdrew from Sierra Leone not long after (Fuchs 107). Aside from an unwillingness to risk death, Machiavelli argues that mercenaries are ineffective because they lack the discipline and organization of more professional forces (The Prince 43). Whereas Gurkha Security Guards demonstrated the validity of Machiavelli’s concern about lack of dedication, Executive Outcomes demonstrated that mercenaries can prove highly capable in combat. The government was losing the war in Sierra Leone until EO, the only mercenary group involved in actual combat, were introduced (Francis 327), replacing the private security company Gurkha Security Guards. After just nine months, they helped the government to drive the rebels from the capital as well as assorted resource rich regions (Fuchs 108). Moreover, much of the appeal modern mercenaries hold for African countries has to do with their level of discipline and organization (Grundy 299-300).

Machiavelli did seem to accurately explain EO’s success in Sierra Leone when he argued that armies comprising a mixture of mercenaries and national forces is better than purely mercenary or auxiliary armed forces, even if his argument that native troops will inevitably prove more capable in combat than combined forces is inapplicable (The Prince 50). In Sierra Leone, mercenaries’ combat experience and professionalism complimented the understanding of the terrain only local fighters could provide (Fuchs 108).

Even when mercenaries prove capable, Machiavelli argues that they are no better for their employers, because the less capable mercenary generals are the more likely they are to prove subversive (The Prince 44). At the very least, when they do betray their employers, they are more likely to be successful.

As the results of warfare have become increasingly determined by technology, highly trained specialists have become uniquely valuable in modern warfare, and impoverished—largely African--states lacking these specialists have to hire them from more developed states veterans (Grundy 308; Joenniemi 194), mercenaries or otherwise. As a result, there are now fewer mercenaries, because the required skillset to appeal to clients has become more demanding, and those wishing to employ mercenaries today lack the buyer’s market present in Machiavelli’s time (Grundy 308).

*Unrestrained Methods

Mercenaries engaging in norm-violating actions may result from the dearth of restrictions imposed upon them. Machiavelli notes that enlisting foreign forces, like private military companies, deprives the government of control over recruitment and firing (The Art of War 21). Executive Outcomes (Francis 326) and Sandline (Creehan 6-7) alike claim that they self-regulate themselves, only accepting contracts from legitimate governments. It is in private military companies long term interests to abide by humanitarian norms in order to avoid contributing to their negative reputation, or at least appear to(Patterson 169-170). While both sides in the Sierra Leone were problematic, even Aguilar, who remained skeptical of self-regulation, acknowledged that the governments’ lack of credibility and brutal methods of suppressing rebellion, were not so objectionable as the atrocities committed by the Revolutionary United Front (Aguilar 5).

A lack of concrete restraints on mercenaries may enable mercenaries to commit atrocities themselves. Machiavelli observed that in Renaissance Italy, newly unemployed “companies” united together in order to extort loot from small towns and the countryside in his own Renaissance Italy (The Art of War 14). Despite the generally widespread distaste for mercenaries in Africa, where they were used as a tool for sustaining colonialism (Joenniemi 190), Executive Outcomes became popular in Sierra Leone for combating the rampant atrocities committed by the rebels and soldiers lacking the basic constraint of professionalism (Francis 327), even if Executive Outcomes did impose high civilian casualties in an effort to rescue Lifeguard Security private security company personnel guarding mines (Francis 332). An examination of the less successful Gurkha Security Guards demonstrates that commendable conduct cannot always be expected from private security companies. Despite their general reluctance to engage in combat, after the Gurkha Security Guard’s commander was killed, his subordinates’ attempts to retrieve his body escalated to involve indiscriminate killing and torture, drawing the ire of the Government and undisciplined national forces alike (Francis 332). The preexisting lack of constraint on violence in lawless weak states where mercenaries predominantly operate may contribute to their lack of respect for international law (Patterson 173). In Sierra Leone’s context of undisciplined regular forces and unconstrained mercenaries, auxiliaries may represent the only chance for imposing consequences for humanitarian abuses. United Nations peacekeepers in Sierra Leone held trials for rebels and government forces alike (Aguilar 5), though mercenaries remain beyond the reach of the United Nations due to the problems inherent in applying international agreements on legitimate combat to non-state international corporations (Creehan 6).

A lack of control over mercenaries' controversial tactics may also be part of their appeal to states, though this may apply more to cases in which the government employing mercenaries sends them to intervene in another country. Because mercenaries have less observable connections to their state employers than other forces, they represent a useful tool for deniable intervention (Joenniemi 190).

In a globalized Post-Cold War context, unilateral action has become politically untenable, making mercenaries highly useful for wealthy Western powers unwilling to engage in an unpopular intervention without the cover provided by deniability (Francis 322-323; Joenniemi 190). Moreover, mercenaries enable states to avoid the risk of scandals surrounding human rights abuses committed by their own, somewhat undisciplined forces, if they delegate the use of force to a deniable proxy (Francis 333). Still, this deniable status of mercenaries is unsustainable. Blame for the actions of mercenaries is increasingly laid at the feet of those who hired them (Joenniemi 195).

Mercenaries operating in Africa may receive covert support from Western countries in order to avoid blame for engaging in norm-violating actions themselves (Francis 333). A potential example from Sierra Leone would be the Sandline Affair. Sandline’s mass shipment of arms to Sierra Leone violated a United Nations embargo, but it claimed that it did so with the support of the Foreign Office in the United Kingdom, Sandline’s home country (Creehan 6). Moreover, the fact that the weapons were being sent to predominatnly Nigerian ECOMOG auxiliaries indicates that it might also violate a United Nations embargo of weapons shipments to Nigeria (Olonisakin 146). Most likely the Sandline affair does represent state support for controversial actions taken by mercenaries, followed by states exploiting deniability after the fact (Francis 334; Fuchs 112-113). At the very least, Sandline’s disregard for the United Nations arms embargo indicates a lack of concern for international law (Olonisakin 147), just as mercenaries’ acceptance of illicit conflict diamonds as payment in Sierra Leone does (Aguilar 5; Fuchs 106).

Joenniemi, writing in the 1970s, distinguishes mercenaries from what Machiavelli would call auxiliaries—forces employed by one state to fight for another state (The Prince 48, Grundy 307)--in terms of the “visibility” of connections to their employers (Joenniemi 191-192). Aside from the increasing openness with which mercenaries have operated since Joenniemi’s time, this distinction would be problematic for the purposes of this essay—and to a certain extent the work of Machiavelli himself—given its focus on the use of mercenaries alongside more regular forces and within their employers’ own borders. However, there is still reason for those employing mercenaries within their own borders to be concerned that foreign mercenaries will maintain connections to their country of origin.

*Undermining State Legitimacy

Mercenaries may also, paradoxically, present a threat to the state as a result of effectively preserving its security. Delegating the use of force to the point that private security companies are the primary provider of security threatens to undermine the legitimacy of the state, an endemic problem leading to long term instability (Fuchs 118; Francis 332). In Sierra Leone, mercenaries commandeered key state capabilities. Not only did Executive Outcomes become the primary guarantor of security, but it supplanted the government’s information network with its own propaganda (Francis 332). Rebellions may be encourage by a lack of perceived strength and legitimacy in states like Sierra Leone, but using mercenaries to address a mercenary threat only worsens the underlying lack of legitimacy (Aguilar 5). However, in cases like Sierra Leone, the alternative to recruiting mercenaries may have even more dramatic consequences for the state’s monopoly on force. The initial inability of the government to provide security from atrocities committed by the rebels seriously undermined the legitimacy of the state (Francis 325).

Historically, mercenaries have also enabled increasing centralization of the control of force, when a political leader pays mercenaries to establish an army loyal to him personally, which he can use to eliminate his domestic rivals (Joenniemi 186-187). The state leader may appeal to foreign mercenaries instead of the people of their own nation, if the mercenaries become the group whose support is most critical to remaining in power. Machiavelli may have alluded to this basic issue when he argued that leaders who must rely on external forces to prop up their rule are more likely to be overthrown by their own civilians (The Prince 44; Grundy 298), but it elicits more concern in the present context where popular government is considered vital, and so the people are more likely to resist such an unjust state of affairs (Grundy 305). Modern day mercenaries pursuing mineral interests are particularly likely to provoke such issues (Francis 323).

*Viable Alternatives

Regardless of how many examples of dysfunctional mercenary behavior there are, if alternative armed forces prove no better, then mercenaries have been singled out for judgement unfairly. Machiavelli argues that lawful arming of citizens will never result in their commanders threatening the political leader (The Art of War 24). Machiavelli does qualify his statements of faith in regular commanders, however, arguing that legal controls must be imposed on them in order to ensure their loyalty (The Prince 44), and that rotating the heads of military companies may be necessary to prevent militiamen from developing greater loyalty to their commanders than their political leaders (The Art of War 31), while such coup-proofing measures may be unfeasible with mercenaries. Machiavelli attempts to address concerns that militia men will lack sufficient martial capabilities as a result of being forcibly impressed into service and lacking the experience of full time mercenaries, arguing that militias must be recruited from those willing but not eager to do their duty for their prince (The Art of War 23). Joenniemmi argues that national military forces are more reliable because they can be organized around unambiguous and complete chains of command preventing independent action (189).

Grundy criticizes Machiavelli’s depiction of national armies will prove easier to control than mercenaries due to a sense of patriotism, noting that African nations have been subjected to many coups even in the absence of mercenaries (302), and arguing that in countries characterized by ethnic diversity soldiers may identify with their own local communities instead of the nation as a whole, but still concludes that in typical circumstances the mercenaries will prove more trustworthy (303). In the event that a coup emerges within the national military, private security companies may prove particularly well suited to countering such a coup, as they may be mobilized on shorter notice than alternatives likes auxiliaries even from neighboring nations (Grundy 307).

A number of coups emerged from the national military in Sierra Leone during the conflict. Protests of what the poorly equipped Sierra Leonean military forces considered an unwinnable war against the rebels eventually escalated to the point of enabling Captain Valentine Strasser to seize power on April 26, 1992 (Fuchs 106-107), only for him to be overthrown by his own deputy, Brigadier Juulio Maada Bio in 1996 (Francis 329; Fuchs 109). The deputy allowed Ahmed Tejan Kabbh to be elected (Fuchs 109). After displacing President Kabbah, Major Korma went a step further and forged an alliance with the rebels, after which he released prisoners who began contributing to the war crimes that made the Revolutionary United Front rebels so infamous (Olonisakin 147). The fallout continued even after, with the execution of military officers involved in Korma’s coup provoking yet more internal conflict within the military in late 1998 (Fuchs 113). Machiavelli did argue that armed forces are likely to present a threat to unarmed leaders unless they are highly capable, and leaders are unlikely to trust their own armed forces (The Prince 52).

CONCLUSION

Mercenaries have clearly diversified their capabilities, and the roles they play in conflict, since Machiavelli’s time. While mercenaries may initially seem to cost reasonable fees compared to other armed forces, mercenaries primarily operate in impoverished conflict prone states incapable of paying mercenaries, which mercenaries can leverage to provide vastly more valuable access to resources. In this respect, Machiavelli’s accusations of greed hold, even if the circumstances have changed. The combat effectiveness of mercenaries is another matter. Because modern mercenaries are primarily veterans trained by highly professional militaries sent to aid weak states, they are often more capable than the national militaries they fight alongside, in contrast to Machiavelli’s claims. Machiavelli’s criticism of mercenaries as unwilling to risk their lives for profit holds, however. Finally, although Machiavelli did not deliberate on this point, it seems that even where mercenaries are highly successful at providing security, this will undermine the legitimacy of the state, because mercenaries are considered separate from the state, preventing the state from receiving credit for increased security. At the same time, this deniability may enable states to utilize mercenaries to accomplish controversial actions that would otherwise be politically untenable. While there is some truth to the characterization of mercenaries as behaving in a lawless and brutal fashion, disciplined mercenaries using brutal tactics may be less prone to atrocities and betrayal of their employers than undisciplined weak state forces, which may disregard the chain of command for their own reasons. Ultimately, it Machiavelli’s basic characterization of mercenaries still applies for the most part, but the present environment greatly complicates these issues.

WORKS CITED

Aguilar, Francisco. “Mercenaries Are Not the Answer.” Harvard International Review, vol. 24, no. 3, 2002, p. 5.

Branovic, Zeljko. “PSD User Manual and Coding Scheme.” Data on Armed Conflict and Security, 2011.

Collaborative Research Center Berlin. “Private Security Database Version 4: 1990-2007.” Data on Armed Conflict and Security, 2011.

Creehan, Sean. “Soldiers of Fortune 500: International Mercenaries.” Harvard International Review, vol. 23, no. 4, 2002, pp. 6-7.

Francis, David J. “Mercenary Intervention in Sierra Leone: Providing National Security or International Exploitation.” Third World Quarterly, vol. 20, no. 2, 1999, pp. 319-338.

Fuchs, Alice E. “Searching for Resources, Offering Security… Private Military Companies in Sierra Leone.” Private Military and Security Companies: Chances, Problems, Pitfalls, and Prospects, edited by Thomas Jager and Gerhard Kummel, VS Verlag für Sozialwissenschaften, 2007, pp. 105-120.

Grundy, Kenneth W. “On Machiavelli and the Mercenaries.” The Journal of Modern African Studies, vol. 6, no. 3, 1968, pp. 295-310.

Joenniemi, Pertti. “Two Models of Mercenarism: Historical and Contemporary.” Instant Research on Peace and Violence, vol. 7, no. 3/4, 1977, pp. 184-196.

Machiavelli, Niccolo. “Book I.” The Art of War, translated by Christopher Lynch, University of Chicago Press, 2003, pp. 7-32.

Machiavelli, Niccolo. “The Different Types of Army and Mercenary Troops.” The Prince, edited by Quentin Skinner and Russell Price, Cambridge University Press, 1988, pp. 42-47.

Machiavelli, Niccolo. “Auxiliaries, Mixed Troops, and Native Troops.” The Prince, edited by Quentin Skinner and Russell Price, Cambridge University Press, 1988, pp. 48-51.

Machiavelli, Niccolo. “How a Ruler Should Act Concerning Military Matters.” The Prince, edited by Quentin Skinner and Russell Price, Cambridge University Press, 1988, pp. 51-54.

Olonisakin, Funmi. “Mercenaries Fill the Vaccuum.” The World Today, Royal Institute of International Affairs, 1998, pp. 146-148.

Patterson, Malcolm H. “Six Prominent Vulnerabilities.” Privatising Peace: A Corporate Adjunct to United Nations Peacekeeping and Humanitarian Operations, Palgrave Macmillan, 2009, pp. 167-175.